Housing Segregation

Learn More About Housing Segregation

“The Color of Law” by Richard Rothstein served as the initial impetus and a great deal of inspiration for this article. If you want the full story of the egregious extent that all levels of US government and society went towards creating segregation then get yourself a copy. You can even check it out at the Austin Public Library.Housing segregation is neither natural nor unique to Austin. Rather it is something that has been intentionally created and enforced through local, state, and federal laws and agencies. It took every conceivable form and its remnants continue to exist today. Our country’s wounds are deep, have not ended, and they still have long to heal.

The forms it took are as numerous and creative as you can imagine. From local racial and euclidean zoning, neighborhood associations, and racial deed restrictions (aka. covenants). To state and country-wide highway expansion. To federal housing loans, public housing, and redlining. To the free market exploiting segregation in the form of blockbusting, contract sales, and 2008’s subprime mortgage crisis. Racist and exclusionary housing practices are not over either; recently Navy FCU was accused of systematically denying loan applications to qualified Black Americans who served in our armed forces.

Intentional and legalized housing segregation continues to plague our cities and towns today.

While many banks also approved White applicants at higher rates than Black borrowers, the nearly 29-percentage-point gap in Navy Federal’s approval rates was the widest of any of the 50 lenders that originated the most mortgage loans last year.

The disparity remains even among White and Black applicants who had similar incomes and debt-to-income ratios. Notably, Navy Federal approved a slightly higher percentage of applications from White borrowers making less than $62,000 a year than it did of Black borrowers making $140,000 or more.

A Note on The Impacts on People

Below we describe the significant ways that our government and society created segregation both in Austin and throughout the US. But equally important is to keep in mind how the people who were victims of these policies were forced to live. They were living in poorly constructed housing that was intentionally placed far from work and “white” society. Despite this they’d often be paying much more for housing than other Americans due to limited options, and higher interest rates from private loans. As a result they’d often be forced to work multiple jobs, take on extra roommates, and have little time or energy to maintain their already poorly constructed housing. They’d have their roads less paved, their sewers less serviced, and other utilities and services neglected.

Many racist stereotypes that exist today come from these conditions. Conditions that are forced on Black Americans and immigrant populations throughout our history. But as is often the case in America, Black Americans seem to get the worst of it; and we must do much better.

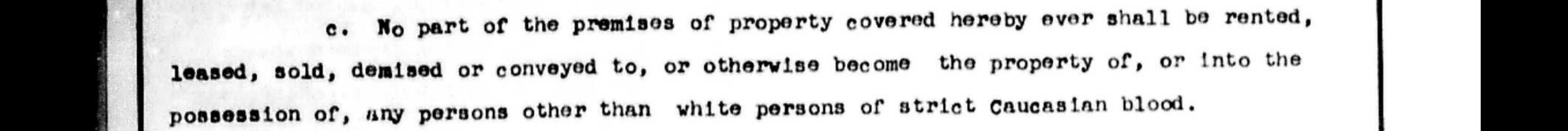

Deed Restrictions / Racial Covenants

If you live in a single family home on the west side of Austin it is very likely that your property has a deed restriction. It’s likely old, filed with the city, and was provided by your title company when you closed on your home. It may detail various things you can and cannot do with your propety from upkeep, to the colors you can paint your home, and the skin color or ethnicity of who is allowed to live in it.

Such restrictions as the one featured above were legal until 1948 when the Supreme Court case Shelley v. Kramer ruled them illegal. Except that the Federal Housing Authority which issued home loans kept issuing them to land owners who had racial covenants in their deed restrictions. This practice continued for over a year until Philip Perlman, the US Solicitor General, instituted a policy that prevented the FHA from giving out loans to such properties starting on February 15, 1950. This announcement was given with a grace period presumably so that racists could rush in any remaining racial covenants before the deadline and be grandfathered in.

Except it didn’t end here either. These covenants were then quickly replaced with prohibitively expensive “damages” that would be charged to land owners who violated a deed restriction and sold land or housing to non-whites. The Supreme Court banned this circumvention in the 1953 case Barrows v. Jackson.

Despite the ultimate unenforceability of any racial covenants in deed restrictions post-1953 they were still able to be included in deed restrictions until a federal appeals court ruled in 1972 that they violated the Fair Housing Act. If they couldn’t be enforced such racist covenants could at least clearly communicate to would-be home buyers who was welcome and who was not.

Mapping segregation

Many excellent people are working across the US to map racial covenants in their cities. No such attempt yet exists in Austin.Neighborhood Associations

Neighborhood Associations came into fashion around the 1920s and went hand in hand with racial covenants in deed restrictions by allowing neighbors to enforce racial covenants. Prior to this a deed restriction was between the seller of a house, and the purchaser of a house. If these two parties decided to not be racist then a house could simply be sold or rented to whoever was wanting to buy or live in it as only these parties could enforce the racial covenant.

This practice was wide-spread and the difficulty of finding and reading through old deed restrictions has unfortunately left the data on it incomplete. Yet data and examples are still abundant. According to “The Color of Law” by Richard Rothstein (p. 80) a survey of 300 developments built between 1935-1947 in Queens, Nassau, and Westchester Counties found that 56% of all of them had racial covenants; as did 85% of large developments (75 or more units).

[..] many subdivision developers created a community association before putting homes up for initial sale, and they made membership in it a condition of purchase. Association bylaws usually included a whites-only clause

Public Housing

In 1933 the US Government started responding to The Great Depression’s significant lack of affordable housing by constructing public housing as part of a series of progressive reforms known as The New Deal. Initially this was done at the federal level under the Public Works Administration (PWA) but shortly thereafter construction would be done at the state level with these projects being approved and funded by the federal United States Housing Authority (USHA).

These housing programs was simultaneously a progressive feat of socialized care for white Americans while also being a driver of segregation, inequity, and upheaval for non-white Americans. It accomplished this through policies of:

- Building racially segregated housing projects from the very beginning and in Austin of course; such as the Santa Rita Courts for Mexican Americans, Rosewood Courts for Black Americans, and Chalmers Court for white Americans.

- Wholesale demolition of integrated neighborhoods under the auspices of “slum clearance”.

- Enforcing neighborhood “composition” rules which turned integrated neighborhoods into segregated neighborhoods.

- Allowing for poor build quality in non-white neighborhoods (“The Color of Law”, p. 33).

In fact the first USHA housing projects were constructed in Austin, TX. These projects involved creating separate white, Mexican, and Black housing projects. The white project would be placed closest to downtown, while the Mexican and Black neighborhoods would be placed on the then-outskirts of the city near heavy industry. Further cementing Austin’s 1928 master plan to segregate the previously integrated city.

Highway Construction

This section/topic is incomplete. If you have some knowledge on this subject please help out by editing this page.